Introduction

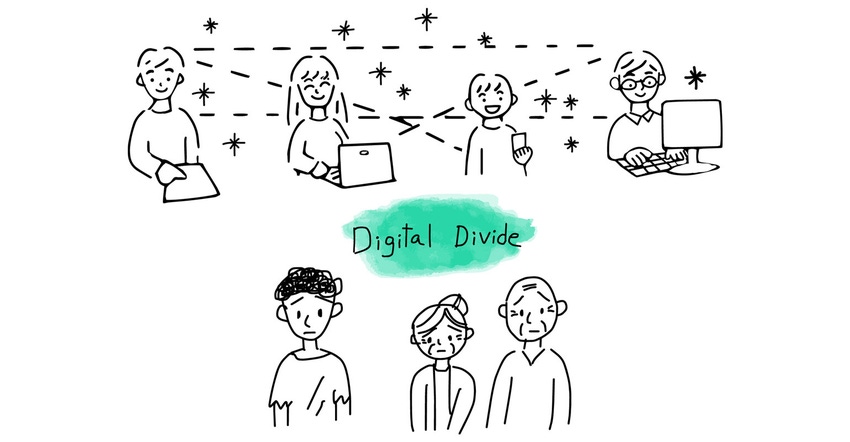

Information technology forms an essential part of homes and work places in many parts of the world. The use of informational technology has grown and continues to grow at a very high rate. Even with this trend, some segments of the population remain disconnected. Unequal access to information technology attributed to gender, age, ethnicity, race, income, and geographical location has been summed up as “digital divide.” The term relates to both social and economic inequality between different groups of people.

At a country level, the inequality is between geographical areas, businesses, households, and individuals. Global digital divide relates to the divide between countries or regions, evaluating the technological gap between developed and developing countries at the international level (MBA & Fitch, 2007).

The Concept of Digital Divide

The phrase describes the gap between those who have access and skills to use information and communication technology and those who lack the same access and skills within a community, society, or geographical area. Many reasons have been cited for the existence of digital divide. Income disparity is one of the reasons since internet use increases with increase in the level of income.

Moreover, economic barriers and poverty increase the persistence of the digital divide because they limit the people’s ability in using upcoming technologies. Nevertheless, research has indicated that digital divide cannot be lessened by availing the required equipment because it goes beyond accessibility. Utilization and reception of information are the other issues that need to be addressed (Warschauer, 2004).

In a research conducted by Pew Research Centre age, disability, level of education, household income and the type of the community are some of the reasons attached to lack of technology use. Irrelevance of internet, ease of use, the high cost of buying a computer and internet connection, and accessibility of internet are some of the reasons cited for not using internet. The research established a strong correlation between internet use and age.

Forty four percent of Americans above the age of 65 do not use internet and they represent 49% of the number of Americans who do not use internet. This proportion did not express interest in using internet and 63% indicated that they would need assistance if they were to use internet. The research indicated limited home access to internet as a reason for not using internet while Hispanics, blacks, and people with low education and income level are the likely groups to rely on internet outside their homes (Zickuhr, 2013). The research findings point to the persistence of digital divide even with the implementation of various proposed solutions

Effectiveness of Solutions to Digital Divide

Research in past has measured digital divide in terms of the number of people who have internet access and those who do not have access to the internet. Based on this narrow definition increasing access to internet through provision of information and communication infrastructure is one recommendation that various governments have worked hard to implement.

In a view to address digital divide in Atlanta, community technology centers were initiated where citizens were exposed to the internet and would learn something about computers and computer applications. In 1999, the city’s mayor launched the Cyber Centers initiative, which would to take computers, internet, and fundamental computer literacy to the low-income neighborhood. The initiative target was to bridge the digital divide gap between the high and low-income earners (Kvasny & Keil, 2006).

The centers were located in extreme poverty areas but their design did not cater for labor force development needs though the project’s executive director stated that the skills they were giving were good enough and would enable people who acquired these skills to apply for jobs requiring computer skills. The initiative successfully reached to residents forming the low-income group who gained computer skills and achieved the broader goal of enhancing the quality of life.

The program attracted a lot of attention from both the local and international community because it was the first digital divide programme in United States. Some residents felt that the skills they received were too basic and needed more skills to increase their competition in the job market, the knowledge made them desire improvements such as buying personal computers, and those with computers at home needed access to high-speed internet. Therefore, the program was successful in providing computer skills but it was a short run solution and reproduced digital divide among those who took part in the initiative (Kvasny & Keil, 2006).

LaGrange is a town whose population is characterized by low levels of education, single-parent families, minority races, people living with disabilities and the elderly. The town reflects the characteristics of people with little access to information technology. The mayor and other city officials noted an economic boom facilitated by Internet in 1999 and put in place an initiative aimed at providing households’ with free high-speed internet connectivity.

The initiative provided free internet through the set-top box used to provide the digital cable service to households. The initiative rolled out with partnership with the WorldGate system and by April 2001, almost half of the eligible households had installed the system. The mayor was categorically quoted saying that charging for the service would mean those with computers at home and internet access would be the likely beneficiaries further widening the digital divide gap (Keil, Meader, & Kvasny 2003).

The initiative incorporated three videos for the purposes of training that covered keyboarding skills, email use, and basic instructions on how to use the internet. The target was to realize economic development through acquisition of skills in information communication technology. The targeted group for this initiative frustrated the initiative because they expressed little interest in the internet TV. Surprisingly, the wealthy expressed greater interest in the initiative.

The targeted profits were not realized and put WorldGate in a financial crisis, which meant that the project was discontinued. The project aimed at providing free internet access to people who did not have it by utilizing the existing infrastructure but suffered setback due to the low interest from the targeted group. The initiative received a lot of praise but was a failure since it ended up being terminated (Po-An Hsieh et al, 2012).

Massachusetts Institute of Technology through the IMARA organization funds opened a wide range of outreach programs to address the Global digital divide gap. The organization seeks to put in place continuing and sustainable solutions aimed at increasing the accessibility of education technology and resources locally and abroad. The program is an initiative of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT and is staffed by volunteers from MIT who donate, install and train on information technology in areas such as Boston, Kenya, and Fiji Islands (Fizz, 2011).

The target population for the project is the underprivileged communities for sustainable education through technology. CommuniTech initiative is part of the MIT initiative that began by refurbishing computers that had been donated earlier and issuing them to underprivileged and marginalized people but soon after they realized that in that way, their initiative was not sustainable. The beneficiaries had to have some training for them to comfortably use the computers and therefore the initiative began introductory computer training to those who had received computers.

The initiative continues to donate and offer computer training to beneficiaries (Fizz, 2011). In terms of addressing digital divide, the initiative was not successful in the sense that it avails the basic infrastructure and training but it fails to address the issue of internet access, which is a component of digital divide. Given that the beneficiaries are poor, they may not be able to pay for internet and they remain locked out of the high-speed internet connection.

The government of New Delhi in partnership with an information technology corporation rolled out a project that was known as “Hole –in-the-Wall” whose aim was to provide internet access to street children. A kiosk with five-station computers was placed in one of slums located in New Delhi. Computers were placed inside but the monitors protruded in the walls through holes. Computers and internet connections were kept running from the inside by a volunteer.

The program was based on theory of minimally invasive education and they operated without an instructor or a teacher to enable the street children learn on their own. Reports on the project stated that many children visited the kiosk and taught themselves the basic operations of a computer and many researchers were in support of the project (Warschauer, 2002). Given that no instructor was availed, the children only learnt how draw paint diagrams and play computer games.

Some parents within the neighborhood did not welcome the initiative based on absence of an instructor and some children neglected their studies in that they spent most of their time playing games on the computers. The project failed to meet its goal since internet access was hardly available. Generally, the community viewed the project as ineffective in meeting its goal (Arora, 2010).

The United States Agency for International development decided to fund an international donor project that would donate a computer laboratory to a main Egyptian University through its college of education. The project target was to create a teacher-training program that would serve as model in computer-assisted learning within a single department.

Sustainability of the project required the Egyptian University to manage all subsequent expenses and operations that included internet access, operation of the computer laboratory, and maintaining the local area network. The university came up with the proposal and state of the art equipment were purchased based on the proposal. Before the installation of the equipment it was s clear that expenses would be a burden for the university and the project faced resistance from other departments who hardly had enough computers.

Many challenges arose more so because the department could not justify the spending so much money on one project while other projects barely received enough funding. The equipment were installed more than one year after their arrival at a time that they had lost a considerable proportion of their market value (Warschauer, 2004).

All the initiatives described above aimed at providing solutions to the problem of digital divide and improve lives of people in low-income areas through access to information communication technology. The likely source of the various failures recorded from the projects can be attributed to the reason that they sought to narrow the digital divide gap by providing the necessary equipment.

Digital divide is defined not only by accessibility to computers and internet but also by other additional resources that would allow people to embrace the initiatives. According to Barzillai-Nahon (2006), policy makers err by relying on simplistic measures of the digital divide in coming up with projects aimed at addressing the digital divide. He points out that policy makers should rely on comprehensive indices in measuring digital divide for them to come up with suitable policies.

Recent research indicate that in developing countries internet use is wide spread among the high-income group who are educated and are mostly found in the urban areas. High literacy levels are attributed to increased internet use among this segment of the population. On this basis, it has been suggested that a solution to digital divide partly requires developing countries to first increase literacy levels, computer skills, and technical competency among the low-income earners and the rural population for them to effectively use information communication technology.

Pick and Azari (2008) suggest that there is strong correlation between a democratic polity and internet use, lesser government control increase the level of internet use in a given country. The authors established that prioritization of information communication technology by the government is a major step in bridging the digital divide gap. Therefore, the authors advocated for increasing the accessibility of education and digital literacy, women empowerment to embrace ICT, and investment in research and development in some selected areas and regions as a better approach to digital divide (Pick and Azari, 2008).

The 2011’s edition of Cyber Monday recorded tremendously large sales figures, which is evidence that America is online. However, Crawford (2011) argues that this event was evidence to a new form of digital divide with dire implications to the economy and society. Politics, health, and entertainment are going online and there is a risk that many will be left behind.

With time, it is likely that job interviews will be conducted via video conferencing to save time and cost. While not all Americans have access to high-speed internet, it means that many will be left out of job opportunities. The mobile devices that the low-income group own cannot substitute cable high-speed internet (Crawford, 2011). Therefore, digital divide as we move into the future may create more divides in the society.

Conclusion

The concept of digital divide is very complex since with advancement of information communication technology, it presents new challenges each day. Age, gender, type of community, level of income, and geographical location are some factors that influence access to internet connectivity. As illustrated, various initiatives in the past have solved the problem of digital divide partially leaving some areas unattended, thus other than solving the initiatives have reinforced digital divide gap.

Researchers have cited wrong measurement of digital divide as the probable reason why many policies have failed. Therefore, to solve the problem of digital divide policy makers should increase accessibility to ICT infrastructure and educate communities on how to use information on the internet based on research data employing the right index in measuring digital divide. Further, the underlying factors such as level of income should be addressed to guarantee long-term solution to digital divide.

Reference List

Arora, P. (2010). Hope‐in‐the‐Wall? A digital promise for free learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(5), 689-702.

Barzilai-Nahon, K. 2006. Gaps and bits: Conceptualizing measurements for digital divide/s. The information society, 22(5), 269-278.

Crawford, S.P. 2011. The New Digital Divide, New York Times. Online <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/opinion/sunday/internet-access-and-the-new-divide.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0> [Accessed on May 23 2014]

Fizz, R. 2011. CommuniTech Works Locally to Bridge the Digital Divide. Online <http://ist.mit.edu/news/communitech> [Accessed on May 23 2014]

Keil, M., Meader, G. W., & Kvasny, L. (2003, January). Bridging the digital divide: The story of the free internet initiative in lagrange, georgia. In System Sciences, 2003. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on (pp. 10-pp). IEEE.

Kvasny, L., & Keil, M. 2006. The challenges of redressing the digital divide: A tale of two US cities. Information systems journal, 16(1), Pp. 23-53.

MBA, S. E. F., & Fitch, S. E. 2007. Digital Divide: An Equation Needing a Solution. Lulu. com: Raleigh.

Pick, J. B., & Azari, R. (2008). Global digital divide: Influence of socioeconomic, governmental, and accessibility factors on information technology. Information Technology for Development, 14(2), 91-115.

Po-An Hsieh, J. J., Keil, M., Holmström, J., & Kvasny, L. (2012). The Bumpy Road to Universal Access: An Actor-Network Analysis of a US Municipal Broadband Internet Initiative. The Information Society, 28(4), 264-283.

Warschauer, M. (2002). Re-conceptualizing the digital divide. First Monday, 7(7).

Warschauer, M. (2004). Technology and social inclusion: Rethinking the digital divide. MIT press: Cambridge.

Zickuhr,K. 2013. Who’s not online and why. Online <http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/09/25/whos-not-online-and-why/> [Accessed on May 23 2014]

Appendices

Appendix 1: Internet Connectivity in among Adults United States from Pew Research

Appendix 2: Reasons for not Using Internet

Appendix 2: Internet Users by Regions